The eRevolution

Call it The Egyptian Revolution, The eRovolution, iRevolution or Revolution 2.0. In any case, I believe we are watching a revolution that was not only written in Egyptian history, but world history. It will be a case study that I believe will be soon taught in many political science and business schools. On Jan 25th, 2011, the world for the first time has witnessed a revolution that brilliantly leveraged the power of social networking tools to overthrow a corrupt regime. Facebook, twitter and blogs were all used to mobilize people all over Egypt. The 30-year dictatorship regime of Mubarak was overthrown in 18 days of peaceful demonstrations.

On Feb 11th, 2011, US president Barak Obama said:

“There are very few moments in our lives where we have the privilege to witness history taking place. This is one of those moments. This is one of those times. The people of Egypt have spoken, their voices have been heard, and Egypt will never be the same”. Source: Remarks on the Egyptian Revolution

The Spark of The eRevolution

The eRevolution was sparked by a group of young activists on Facebook calling for nationwide demonstrations to restore people’s dignity and ask for reform, freedom and social justice. Through the initiation of different Facebook groups, but mainly the “We are all Khalid Saed” Facebook group that attracted about 80,000 participants, citizens coordinated their ideas and demonstration logistics via group posts, and comments, while communicating heavily on twitter and sometimes cell phone SMS services. Khaled Saed is a young Egyptian who is widely believed to have been murdered by police.

Other Facebook groups were initiated before, during, and after Jan 25th, 2011 to support the logistics and the massive demonstrations that erupted all over Egypt. The “Rasd News Network (R.N.N)” Facebook group was one of the main contributors to the revolution, sending protest updates, news updates and politicians and media reaction.

Any Facebook user whose been part of any of these Facebook Egyptian activist groups or even a Facebook friend of someone who has been part of these groups could see that the revolution started virtually on Facebook a few days prior to the actual physical start of Jan 25th Revolution. The large number of the group posts, user comments, message exchanges, and clear human mobilization were more than enough to indicate the kind and size of protests that would take place later on the 25th.

The Generation Gap

The members of the Egyptian regime had a serious generation gap with the young generation of social networkers. While the average age of the Egyptian Facebook activists was in the 20s, the regime members were in their 60s and 70s and ruled by an 83 years old president. The regime, therefore, was seriously under-qualified to fight a battle it didn’t even comprehend or to even form proper decisions in handling the situation. The government IT workers were mainly hired based on “loyalty” and nepotism, not based on qualifications. Accordingly, the regime with a limited mindset thought that blocking twitter, SMS services and later Facebook access, would cut the communication lines between protestors and the movement organizers.

Getting Around The Internet Filters

Using third party proxies, the young organizers didn’t take long to figure out ways to bypass the Egyptian Internet filters and to be able to once again access Facebook, twitter, YouTube and other Internet sites. The regime did not know what to do next. On the afternoon of Jan 28th, local officials extended their tactics to include cutting all cell phone communication in major cities in Egypt, thinking that this would curb the growing support and flooding of people into the streets of Egypt.

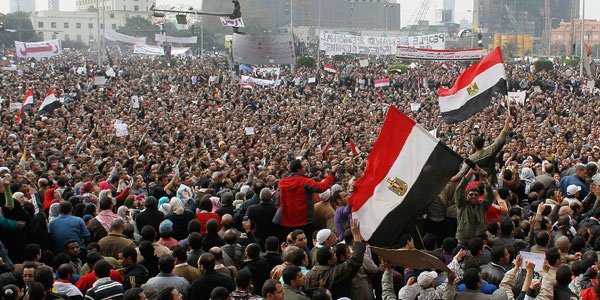

By late evening of Friday Jan 28th, and in another desperate move to stop the massive flood of people into the streets, the Egyptian regime shutdown all Internet access in Egypt; the first Internet blackout of such magnitude in the history of Internet. Unfortunately for the regime however, protesters were already in the streets, flyers were already printed and being handed over to people, and the revolution was forming rapidly. There was not a big need for the Internet for the revolution to gain any more momentum. People in the streets were already aware of where to go and how. The Tahrir Square (or Liberation Square) became the central gathering point for protestors in Cairo. The Al Qaed Ibrahim Mosque was a central point in Alexandria (the second largest city in Egypt), and many other spots around the different Egyptian cities were also recognized as other central gathering points.

Despite the Internet blackout, landline communication was never blocked; Egyptians found another way to access the Internet through old school landlines dial-up Internet services and fax services. Egyptians living outside Egypt would receive faxes through regular landline phones, use Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technologies to convert the fax image into text contents, and post the contents, news and updates into Facebook, twitter and different blogs.

Google in the meantime launched a new service called “speak2tweet”, which allowed Egyptians to call a regular landline number in Cairo and speak their tweet to an IVR/Voice recognition system. The speak2tweet system would then convert the caller voice message into a text tweet.

The Role of TV Media

Satellite channels like Al-Jazeera, BBC, CNN and others played a major role in the revolution by broadcasting live images from Tahrir square, sending live updates and clear messages to protestors on the critical gathering points. That drove the regime into a more desperate situation. The regime started banning journalists from entering the square through the use of thugs and secret police that chased, attacked, and banned journalists from entering the Square or staying in any nearby hotel that could have a camera view to the crowd in Tahrir Square. Little by little, police, with the help of thugs, were able to stop all live feeds from Tahrir Square for a period of time until Al-Jazeera TV channel managed later to sneak a camera to broadcast another feed showing the Square; the regime responded by shutting down all of Al-Jazeera broadcasts from Nilesat (The Egyptian Satellite) and attempting to jam Al-Jazeera signal on other satellites with a footprint coverage in Egypt.

Protestors continued to gain momentum day after day by insisting that they would not leave the Square until the entire Egyptian regime resigns. Close to five million people were in the streets of Egypt (and some other news sources estimate the protestors number closer to eight million), three million protestors were in Cairo alone.

Due to the continuous pressure of protestors, the regime yielded to some of the demands of the crowd, although many believed that the regime was only playing delay tactics and only portrayed a reform. A vice president was appointed, and a new government took over and restored cell phone communication and Internet access as an indication of goodwill.

Restoring back the Internet, however, seemed to have backfired. Egyptians now were able to upload on Facebook and Youtube some of the pictures and video clips showing the massacres conducted by the central police forces and thugs on civilians during the early days of protests; live bullets, snipers, people run by cars, others beaten to death, thugs with machetes, Molotov cocktails thrown on protestors and many other indescribable atrocities.

The Collapse of the Regime

After a few more days of the increasing number of protestors, high national and international pressures, and a total of 18 days of protesting, Omar Suleiman (the recently appointed Egyptian vice president) at 16:02 GMT of Friday Feb 11, 2011 in a 28 seconds statement on state TV said:

“My fellow citizens, in this difficult time that the country is going through, President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak has decided to relieve himself of his position as president and the Supreme Military Council has taken control of the state’s affairs. May God protect us”.

Egypt has spoken; no more tyranny, no more autocracy, no more injustice and no more oppression. The history has been written not only in Egypt, but in the world of social networking as well; the first revolution sparked, managed and orchestrated by social networking, by Facebook, twitter, blogs and YouTube. For the first time in history the eRevolution was born, and for the first time in history the eRevolution became a reality.

“First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win” – Gandhi

A Two-Edge Sword?

The January 25th Egyptian revolution and the resignation of Mubarak on Feb 11 created a new revolution model; an eRevolution. This eRevolution poses a few important questions that could take awhile to answer.

Will this new eRevolution model become a tool for other people to revolt against their dictatorship regimes? Could social networking become a two-edge sword? Or, has it already been one? What if social networking is used by the wrong people or for the wrong reasons? What would constitute a wrong reason or the wrong people? Should there be a line drawn between what should and should not be said or done through social networking or would this by itself constitute a violation to the freedom of speech rights the Egyptian revolution called for?

![If you [Mubarak] were a daemon, it would have been easier to excesses you out](https://famousbloggers.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/mubarak-leave-150x150.jpg)

SEO is Evolving: Trend You Need to Know About [Infographic]

SEO is Evolving: Trend You Need to Know About [Infographic] Importance Of Professional Social Media Services For Businesses

Importance Of Professional Social Media Services For Businesses Social Media Makes Sales Enablement Easy By Showing How Smart Business Can Be

Social Media Makes Sales Enablement Easy By Showing How Smart Business Can Be 14 Tips To Help You In Marketing Your WordPress Site

14 Tips To Help You In Marketing Your WordPress Site

{ 53 Responses }